The foundation of a child’s future health and development is laid in the womb, making pregnancy an important period. Maternal exposure and experiences during this critical period can have long-term impact on the physical and mental health and wellbeing of a child throughout their life course.

In addition to influencing child development by impacting fetal development, maternal health and behavioural risk factors can influence the risk of adverse health outcomes later in life including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and mental health disorders. These risk factors include poor maternal nutrition, smoking during pregnancy, alcohol use and exposure to environmental toxins. On the other hand, good prenatal care, a healthy diet, and other positive behaviours can help promote fetal growth and development and reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes in the child.

It is important to note that the effects of pregnancy on a child's development and life course are not solely determined by the maternal behaviour and experiences. Wider determinants of health including social, economic, and environmental context in which the mother and child live can also have a significant impact on the child's health and development. For example, poverty, lack of access to healthcare, and exposure to violence and air pollution can all increase the risk of adverse health outcomes for both the mother and child. Understanding patterns in health before and during pregnancy is important if we are to narrow the health gap for those who are most vulnerable. Inequalities in maternal and infant outcomes exist, with poorer outcomes experienced by certain groups of women and their babies.

Maternal Health Outcomes

Maternal health is the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the post-partum period. It encompasses the healthcare dimension of preconception, prenatal and postnatal care, to ensure a positive and fulfilling experience, and reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. Each stage should be a positive experience, ensuring women and their babies reach their full potential for health and well-being (WHO, 2023).

Monitoring maternal health outcomes allows us to identify areas where improvements are needed and implement interventions to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. They also allow us to monitor progress towards achieving global health targets, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 3 and 5) and the World Health Organization's (WHO) Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health. These targets include reducing maternal mortality, improving access to maternal health services, and promoting maternal and new-born health.

In this section, we will provide an overview of reproductive health using the general fertility rate indicator, followed by indicators on health behaviours and risk factors in pregnancy, maternal health screening and health care access. Fertility rates are closely tied to growth rates for an area and can be an excellent indicator of future population growth or decline in that area.

a. General Fertility Rate:

General fertility rate (GFR) is an important measure of reproductive health and provides useful insights into the demographic composition and health status of a population. It is the number of live births each year per 1000 women aged 15 to 44 years. GFR is a more refined measure of fertility than the crude birth rate as it considers the age distribution of women in their reproductive years. General fertility rate (GFR) in Bury for the year 2022 is 51.9 per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44 years and significantly higher than England average.

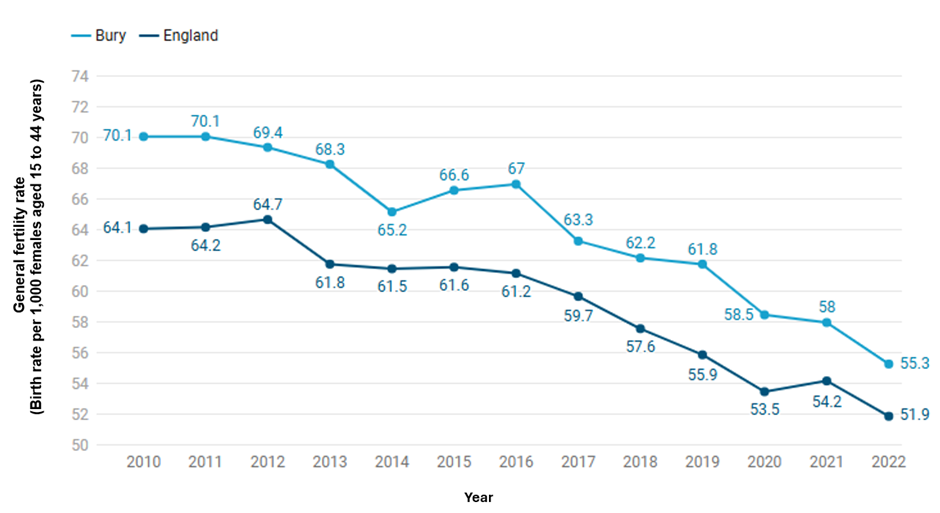

From 2010 to 2022, both Bury and England experienced a consistent decline in general fertility rates. In Bury, the rate decreased from approximately 70.1 births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44 years in 2010 to about 51.9 in 2022. Similarly, England's rate dropped from around 64.1 to 55.3 over the same period. Despite the overall downward trend, Bury consistently had higher fertility rates compared to the national average in England throughout these years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: General Fertility Rate (GFR) by usual area of residence for the years 2010 to 2022 for Bury and England (Child and Maternal Health, 2022)

An area may have higher GFR due to several reasons:

1. Demographic factors: The age distribution and ethnic composition of a local population can influence the GFR. For example, if a local authority has a higher proportion of women of childbearing age, this can increase the number of live births and raise the GFR. This does not appear to be the case for Bury, where 18% of the population is of childbearing age compared with 19.5% in England.

2. Socioeconomic factors: Education levels, employment status, and income can also play a role in determining the GFR. Higher levels of education and income are often associated with lower fertility rates, while areas with higher levels of unemployment and poverty may have higher fertility rates.

3. Cultural factors: Attitudes towards family size and childbearing can vary between regions and communities. For example, some cultural or religious groups may place a strong emphasis on having large families, which can raise the GFR in those areas.

4. Healthcare access: Access to family planning services and healthcare can also impact the GFR. Areas with better access to reproductive health services and education are likely to have lower GFRs compared to areas with limited access.

It is important to note that the GFR can fluctuate over time and may be influenced by short-term events or changes in policy or initiatives. A higher GFR compared to the national level does not necessarily indicate a better or worse standard of living.

b. Preconception

Preconception health is a woman's health before she becomes pregnant. It focuses on factors to protect the health of a baby they might have some time in the future. This section examines indicators relevant to preconception.

Many of the available indicators relate to birth control. This is because physical and mental health outcomes for both the child and mother are better on average when a pregnancy is intentional.

Long-acting reversible contraceptive

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, such as contraceptive injections, implants, the intra-uterine system (IUS) or the intrauterine device (IUD), are highly effective as they do not rely on daily compliance and are more cost effective than condoms and the pill. A strategic priority is to ensure access to the full range of contraception is available to all. An increase in the provision of LARC is a proxy measure for wider access to the range of possible contraceptive methods and should also lead to a reduction in rates of unintended pregnancy. Fingertips measures the provision of LARC but excludes injections with one of the key reasons being that injections are primarily outside local authority contracts.

· Long-acting reversible contraceptive ‘under 25s’

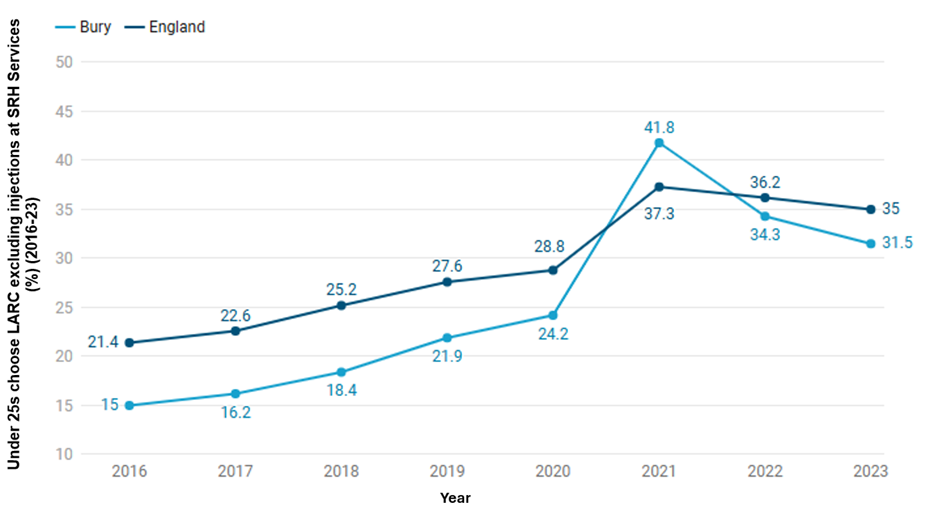

In the year 2023, approximately 31.5% of chose LARC excluding injections at SRH Services, statistically similar to the figure for England of 35%. From 2016 to 2023, Bury saw a significant increase in the percentage of under 25s choosing Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) at Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services, rising from 15.0% in 2016 to a peak of 41.8% in 2021. However, this was followed by a notable decline to 31.5% in 2023. In comparison, England experienced a more gradual increase, starting at 21.4% in 2016 and reaching around 35.0% by 2023. This indicates that while both Bury and England have seen an upward trend in LARC usage among under 25s, Bury experienced a sharper rise and higher peak compared to the national average, followed by a more significant drop in recent years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage of women in contact with Sexual and Reproductive Health Services who choose long acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) excluding injections as their main method of contraception for the years 2014 to 2023 for Bury and England (Sexual & reproductive health profiles, 2023)

Bury has the 8th highest percentage (%) of Under 25s choosing LARC excluding injections at SRH Services in its group of 16 similar local authorities in 2023 with the lowest percentage in Doncaster at 13.8% and highest in Rotherham at 55.5% (Sexual & reproductive health profiles, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level. England data shows a slight deprivation gradient with higher percentage of under 25s choosing LARC excluding injections at SRH Services in the least deprived decile (37.9%) compared to the most deprived decile (33.2%).

· Long-acting reversible contraceptive ‘over 25s’

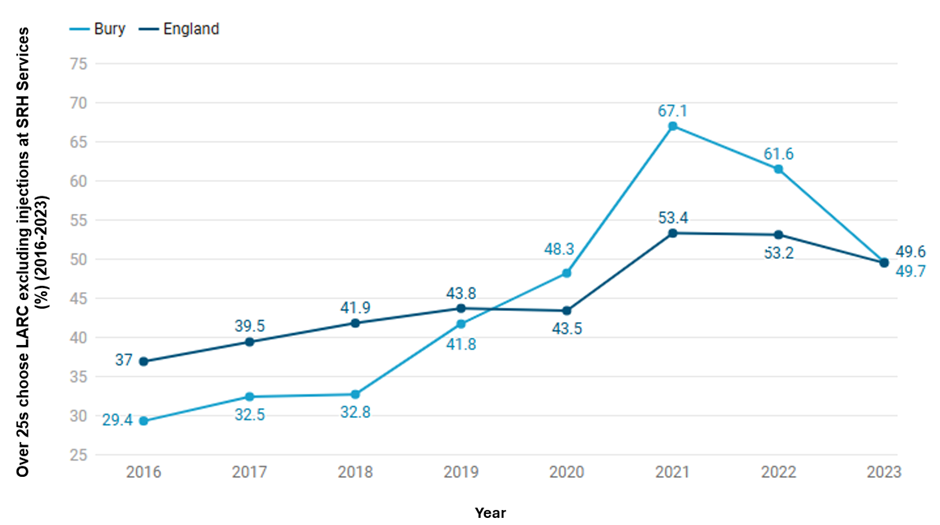

In the year 2023, 49.7% of ‘over 25s’ chose LARC excluding injections at SRH Services, statistically similar to the figure for England of 49.6%. From 2016 to 2023, Bury saw a general upward trend in the percentage of over 25s choosing Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) at Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services, starting at 29.4% in 2016 and peaking at 67.1% in 2021. However, there was a decline to 49.7% by 2023. In comparison, England also experienced an upward trend, beginning at 37.0% in 2016 and reaching 53.4% in 2021, followed by a slight decrease to 49.6% in 2023 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Percentage (%) of over 25s choosing LARC excluding injections at SRH Services for the years 2016 to 2023 for Bury and England (Sexual & Reproductive Health Profiles, 2023)

Bury has the 7th highest percentage (%) of over 25s choosing LARC excluding injections at SRH Services in its group of 16 similar local authorities in 2022, with the highest percentage in Rotherham at 75.3% and lowest in Derby at 35.8% (Sexual & reproductive health profiles, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level and England data does not show any deprivation gradient.

Under 18 conception rates

Maternal age is an important factor for pregnancy outcomes. Younger women are at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. For example, they are less likely to take a folic acid supplement which protects against the risk of neural tube defects such as spina bifida (Bestwick et al, 2014). Babies born to women under the age of 20 are also approximately 20% more likely to be of low birth weight (ONS, 2023). Teenage mothers are less likely to complete their education, are more likely to raise their child alone and in poverty, and are at a greater risk for mental illness than their older counterparts. The infant mortality rate for babies born to teenage mothers is approximately 60% higher than that of babies born to older mothers. The children of teenage mothers are more likely to live in poverty and substandard housing, and to experience accidents and behavioural issues. Raising a child as a teenager is difficult and frequently results in negative outcomes for the baby's health, the mother's emotional health and well-being, and the likelihood of both parent and child living in long-term poverty (OHID, 2023).

During the period 2022/23, 0.5% of the pregnancies in Bury were teenage pregnancies (Percentage of delivery episodes, where the mother is aged under 18 years) statistically similar to 0.6% in England. The percentage of pregnancies in under 18s has been declining both nationally and in Bury (Children and Maternal Health, 2023)

Under 18 conception rate is measured as conceptions in women aged under 18 per 1,000 females aged 15-17 years. The rate for Bury in the year 2021 was 14.4 per 1,000 females aged 15-17 years, statistically similar to the England average of 13.1. There has been a downwards trend in the under 18 conception rates for Bury and England from 1998 to 2021 (Figure 4), however the rates in Bury have remained consistently higher than England during this period. The rate in Bury declined from the peak at 55.6 per 1,000 females in 1998 and gradually declined to 14.4 per 1,000 females in 2021. A recent study has attributed this decline to local areas experiencing less youth unemployment, growing Black or South Asian teenage populations, more educational attainment, unaffordable housing and a lack of available social housing (Heap et al, 2020).

Figure 4: Conceptions in women aged under 18 per 1,000 females aged 15-17 years for the years 1998 to 2021 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2021).

Compared to Bury's closest children's services statistical neighbours, Bury has the third lowest under-18 conception rate in its group of 5 statistical children service neighbours with the highest rate in Stockton-on-tees at 17.4 and lowest in Stockport at 11 (Children and Maternal Health, 2021). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests increasing conception rates with increasing levels of deprivation. The most deprived decile in England has an under-18 conception rate of 17.8 compared with 7.7 in the least deprived decile for the year 2021 (Child and Maternal Health, 2021).

Under 18 conceptions leading to abortion

It is increasingly common for pregnant young women under 18 to have an abortion. Access to family planning and sexual health services, and the availability of independent sector abortion provision, directly affect abortion proportions. More deprived areas in England have both higher conception rates and a lower proportion of under-18 pregnancies ending in abortion.

Most recent data for Bury shows that 66% of under 18 conceptions led to abortion (2021), statistically similar to the figure for England of 53.4%. Figure 5 presents the percentage of conceptions to those aged under 18 years that led to an abortion in Bury and England from the year 1998 to 2021. The percentage of abortions in Bury ranged from 38.6% in 2000 to 71.2% in 2019. From the year 1998 to 2000, there was a decrease in the percentage of abortions from 42.4% to 38.6% and then started to increase again. From the year 2001, the percentage of under 18 conceptions leading to abortion continued to increase from 46.8% to reach a peak of 71.2% in 2019, before decreasing slightly to 70.5% in 2020 and again to 66% in 2021. The large fluctuation in data for Bury may be due to small numbers at the local level.

The trend in England is different from that observed in Bury with less fluctuation in the data ranging from 42.4% to 53.4% from 1998 to 2021. The percentage of abortions in under-18s increased steadily from 42.4% in 1998 to 50.5% in 2007, remaining stable until 2012 at 49.1% before steadily increasing to the peak in 2019 at 54.7%, followed by slight declines in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Percentage (%) of under 18 conceptions leading to abortions for the years 1998 to 2021 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2021).

Bury has the third highest under 18 conceptions leading to abortion in its group of statistical children service neighbours with the lowest percentage in Stockton-on-Tees at 39.3% and the highest in Stockport at 71.2% (Children and Maternal Health, 2021). There are no data on inequalities within Bury but England data suggests decreasing percentage of under 18 conceptions leading to abortion with increasing levels of deprivation. The most deprived decile in England has an under-18 abortion percentage of 46.6% compared with 61.5 in the least deprived decile for the year 2021 (Child and Maternal Health, 2021).

c. Risk and protective factors and health behaviours in pregnancy

Many factors impact a woman’s health in pregnancy. The extent to which these can be modified varies. For example, once a woman is pregnant, factors such as the age at which she will become a mother cannot be modified. There are, however, less healthy behaviours which are often established well before pregnancy. This is the case for dietary and exercise habits, smoking, alcohol and substance misuse and many other factors. Effective action to reduce these risk factors before and during pregnancy can improve outcomes for mothers, babies and their families. As with many aspects of public health, inequalities in maternal and infant outcomes exist, with poorer outcomes experienced by certain groups of women and their babies. These risk factors and the health behaviours will be presented next.

Folic acid supplements before pregnancy

Folic acid (also known as vitamin B9) is essential for the development of a healthy foetus because it reduces the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) like spina bifida. Percentage of pregnant women who started taking folic acid prior to pregnancy as reported at time of booking appointment with a midwife in Bury (20.2%) is lower (statistically significant) than 25.6% in England for 2020/21. This shows an increase of 1.7% for Bury from the previous time period of 2019/20 from 18.5%, and a very slight decrease of 0.1% for England for the same time period to 25.6% (Fingertips 2020).

Smoking

Smoking during pregnancy is associated with a variety of adverse birth outcomes including low birth weight and preterm birth, increased risk of stillbirths, placental problems, restricted head growth and an increased risk of miscarriage. Health and developmental consequences among children have also been linked to prenatal smoke exposure, including poorer lung function, persistent wheezing, and asthma, possibly through DNA methylation and visual difficulties, such as strabismus, refractive errors, and retinopathy.

· Smoking in early pregnancy

Based on the most recent data from 2023/24, 10% of pregnant women in Bury smoked at the time of booking appointment with midwife, lower (statistically significant) than 13.6% in England. No trend data are available for Bury and England. Bury has the eighth lowest percentage of pregnant women smoking at the time of booking appointment with midwife in its group of statistical neighbours, with the lowest percentage in Trafford of 6.3% and highest in Telford and Wrekin at 21.2% (Fingertips 2024).

· Smoking status at time of delivery

This indicator is defined as the number of mothers known to be smokers at the time of delivery as a percentage of all maternities with known smoking status. A maternity is defined as a pregnant woman who gives birth to one or more live or stillborn babies of at least 24 weeks gestation, where the baby is delivered by either a midwife or doctor at home or in an NHS hospital.

The percentage of women who were known smokers at time of delivery has declined in Bury and England over the past decade. In the year 2023/24, the smoking status at the time of delivery in Bury was 7.5%, statistically similar to the England average of 7.4%. From 2010/11 to 2023/24, Bury saw a general downward trend in the percentage of women smoking at the time of delivery, starting at 16.9% in 2010/11 and decreasing to 7.5% in 2023/24. Similarly, England experienced a downward trend, beginning at 13.6% in 2010/11 and reaching 7.5% in 2023/24.

Figure 6: Smoking status at time of delivery during the period 2010/11 to 2023/24 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2024).

Bury has the third lowest percentage (%) of women who are known smokers at the time of delivery in its group of statistical neighbours in 2023/24 (with a statistically significant decreasing trend). The highest percentage is in Stockton-on-Tees at 10.6% and lowest in Stockport at 5.8% (Sexual & reproductive health profiles, 2024). There are no data on inequalities at Bury and England level.

Alcohol

There are no data on alcohol use during pregnancy for Bury and its statistical neighbours. However, data for England are available for early pregnancy, showing that around 4.1% of pregnant women were recorded as drinking alcohol at the time of their booking appointment with a midwife in 2018/19 (Fingertips). Data on inequalities are available for England only. A higher percentage of women (5%) in the least deprived deciles in England drink in early pregnancy compared with the most deprived decile (3.3%). By ethnic groups, the highest percentage of women drinking during early pregnancy were White (4.6%), followed by Mixed (4%), Black (3.7%), and the lowest percentage were Asian (1.8%). Examining data by age of mother for England, as the age of women increases, the percentage of women drinking in early pregnancy increases. A higher proportion of women over 45 years of age (5.6%) drink alcohol in early pregnancy compared with those under 30 years of age (3.6%). Most recent available data from 2018/19 suggests that a lower proportion of women who are first time mothers drink during pregnancy in England (3.6%) compared with those who have a subsequent pregnancy (4.4%).

Drug misuse

There are no data on drug misuse during pregnancy for Bury and its statistical neighbours. However, data for England are available for early pregnancy, showing that 1.4% of pregnant women were recorded as misusing non-medicinal drugs or other unauthorised substances at the time of their booking appointment with a midwife in 2018/19 (Fingertips). Data on inequalities are available for England only. A higher percentage of women (2.8%) in the most deprived deciles in England misuse drugs in early pregnancy compared with the least deprived decile (0.4%). By ethnic groups, the highest percentage of women misusing drugs in early pregnancy for 2018/19 were Mixed (2.7%), followed by Black (1.7%), White (1.4%) and the lowest percentage were Asian (1.2%). Examining data by age of mother for England, as the age decreases, the percentage of women who misuse drugs in early pregnancy increases. The highest proportion of women who misuse drugs in early pregnancy are under 18 years of age (3.1%), compared with those over 45 years of age (1.5%). A slightly lower proportion of women who are first time mothers misuse drugs in early pregnancy (1.2%) compared with those who have a subsequent pregnancy (1.4%).

Obesity

Obesity during pregnancy is measured in Fingertips as the percentage of pregnant women who are obese (BMI>=30kg/m2) at the time of booking appointment with a midwife. Based on the most recent data from 2018/19, 22.6% of pregnant women in Bury were obese, statistically similar to the England average of 22.1%. No trend data are available for Bury and England. Bury has the third highest percentage of pregnant women who are classified as obese in its group of statistical neighbours, with the lowest percentage in Stockport of 20.1% and highest in Calderdale at 24.9% (Fingertips, 2019).

d. Maternal Infectious Disease Screening

Infectious diseases in pregnancy screening (IDPS) offers and recommends screening tests for infectious diseases in pregnancy. The tests are aimed to protect maternal health through early treatment and care, reduce any risk of perinatal transmission and transmission to partner and/or other family members. The three diseases covered by IDPS are HIV, Syphilis and Hepatitis B. There are no publicly available data from IDPS on maternal infectious disease screening.

e. Maternal health care access

Early access to maternity care enables health care providers to identify and treat potential health problems in the mother and infant, resulting in better health outcomes. Early access to maternity care can also help reduce the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight and other adverse pregnancy outcomes including maternal death. Inadequate use of antenatal care has been shown to be strongly independently associated with increased odds of maternal death.

The NHS offers a ‘booking-in’ appointment between 8 to 12 weeks of pregnancy. NICE recommends antenatal booking by 10 weeks of pregnancy. This appointment allows scheduling of ultrasound scan, identification of women who may need more care than usual due to medical history or social circumstances, discussion of antenatal screening, taking blood pressure and measuring the woman's height and weight, identification of risk factors such as smoking and providing support and discussion of the woman's mood and mental health. It also ensures that the mother's information can be shared in a timely manner with the health visiting service, who visits the mother at home during the last three months of her pregnancy to promote health and wellbeing, plan for parenthood and, if necessary, arrange for more intensive postpartum support.

Pregnancies booked at or after 12 weeks are considered ‘late booked’ and late booking is considered a modifiable risk factor for infant mortality. Women booking after 20 weeks of pregnancy are considered at particularly high risk because they have missed the screening window for certain infectious diseases, inherited conditions, and Down's, Edwards and Patau's syndromes.

Early access to maternity care

Early access to maternity care is measured as the percentage of pregnant women who have their booking appointment with a midwife within 10 completed weeks of their pregnancy. In 2023/24, 54.1% of pregnant women in Bury had their first booking appointment within 10 weeks, which is significantly lower than the figure for England at 63.5% for the same period (Figure 7). The percentage of women accessing early maternity care in Bury has fluctuated over time, consistently remaining significantly below the England average. In 2019/20, 41.8% of women in Bury accessed early maternity care. This was followed by a substantial increase of 16.7%, reaching 58.5% in 2020/21. During the same period, England also saw an increase, but to a lesser extent, rising by 7.9% to 68.2% in 2020/21. A slight decrease occurred in 2021/22 for both Bury and England. However, Bury experienced a significant decline in 2022/23, with a reduction of 10.8%, whereas England's rate only decreased by 2.2% during the same period. In 2023/24, Bury saw a notable increase of 10.1%, bringing the rate to 54.1%. Although this increase was higher than the percentage rise seen in England for the same period (2.1%), Bury still remained significantly below the England average. Recent trend data based on the five most recent data points suggests no significant change in trend.

Among Bury’s group of closest statistical neighbours, Bury had the second lowest percentage of early access to maternity care, with the highest access in Calderdale at 70.3% and the lowest in Stockton-on-Tees at 40.8% (Children and Maternal Health, 2024). No inequalities data are available at the Bury level. However, for England, it can be observed that the less deprived the area, the higher the access to early maternity care. In 2023/24, 69.6% of those living in the least deprived decile accessed early maternity care, compared to 56.9% in the most deprived decile (Children and Maternal Health, 2024). Data on ethnic groups are unavailable for Bury. However, for England in 2023/24, the ethnic group with the highest percentage of mothers accessing early maternity care was White at 67.6%. This was followed by Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups and Not Known/Not Stated at 60.2%, Asian at 58.7%, Other ethnic group at 52.1% and Black ethnic group with the lowest percentage at 46.2% (Child and Maternal Health 2024).

Figure 7: Early access to maternity care during the period 2019/20 to 2023/24 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2024).

2. Newborn health and Birth Outcomes

Maternal health is a resource for life and ensures the best start of life for a child. Pregnancy and birth outcomes measure the health and well-being of mothers and babies during and after pregnancy and childbirth. Examining data on these outcomes allows valuable insights into the quality and accessibility of maternal and child healthcare services, as well as broader social and economic determinants of health. Publicly available data on pregnancy and birth outcomes for Bury are presented next.

a. Cesarean section

Caesarean sections (commonly referred to as c-sections) are often required for several maternal and infant reasons. By their nature (i.e. they are used when there are complications) they are likely to be associated with an increased risk of problems.

The percentage of caesarean sections in Bury was 37% in 2022/23 and statistically similar to England average of 37.8%. There has been an increase in percentage of caesarean sections in Bury and England from 2013/14 to 2022/23, with a particularly rapid increase from 2017/18 to 2022/23. In Bury, the percentage of women who had a c-section increased by 12.4% from 24.6% in 2013/14 to 37% in 2022/23. Trend data based on the five most recent data points suggests and increasing and worsening trend.

The percentage of c-sections in England has also been increasing over the same period having also increased by 12.4%, from 25.4% in 2013/14 to 37.8% in 2022/23.

Figure 8: Percentage of c-sections during the period 2013/14 to 2022/23 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2023).

Bury has the fourth highest percentage of c-sections in it's group of children's services statistical neighbours in 2022/23. The highest percentage is in Stockport at 43% and lowest in Calderdale at 31.2% (Children and Maternal Health, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level. Data at the national level suggests that as the levels of deprivation decreases, the percentage of c-sections increase. The percentage of c-section in the most deprived decile in England is 30.2% compared with 33.5% in the least deprived decile (Child and Maternal Health, 2021).

b. Premature births (less than 37 weeks gestation)

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines premature births (also referred as preterm births) as babies born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy are completed (WHO, 2022). Babies may be born prematurely due to spontaneous preterm labour or a medical indication to schedule an induction of labour or caesarean birth early. Premature births can lead to low birth weight that is closely associated with foetal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, stunted growth and cognitive development, and NCDs later in life, among other negative health outcomes.

There is strong evidence that smoking while pregnant and exposure to second-hand smoke can result in premature birth, in addition to many other adverse health effects, such as complications during labour, low birth weight at full term, and an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth (Child and Maternal Health, 2020).

Premature births are measured in Fingertips as crude rate of premature live births (gestational age between 24-36 weeks) and all stillbirths per 1,000 live births and stillbirths.

In 2019-21, the premature birth rate in Bury was 78.2 per 1,000 live births and stillbirths, statistically similar to the England average of 77.9 per 1,000.From the period 2006-08 to 2013-15, premature birth rates in Bury were stable, ranging from a rate of 73 to 71.7 per 1,000 live births and stillbirths. From 2013-15 to 2016-18, the premature birth rates in Bury increased rapidly, from 71.7 to 85.5 per 1,000 live births and stillbirths. This was followed by a decline in 2018-20 to 80.3, followed by a further decline in 2019-21 to 78.2. Throughout the period 2006-08 to 2014-16, premature birth rate in Bury remained below the average for England (although only statistically significant lower for the period 2007-09, 2008-10 and 2013-15). From 2015-17 to 2019-21, the rates in Bury were higher than England average but were not statistically significant.

Similar to Bury, the premature birth rate in England has been fluctuating over time, with some periods of increase and some periods of decrease. During the period 2006-08 to 2010-12, premature birth rate in England decreased gradually from 77.6 to 75.7 per 1,000 live births and stillbirths. From 2010-12 to 2016-18, the premature birth rate in England increased to 81.2 per 1,000 live births and stillbirths. In 2018-20, there was a slight decline to 79.1, and a further decline in 2019-21 to 77.9 in per 1,000 live births and stillbirths.

Premature birth rate in Bury has shown a more rapid increase in recent years than in England, but the most recent data for both areas show a decrease in premature birth rate (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Crude rate of premature live births (gestational age between 24-36 weeks) and all stillbirths per 1,000 live births and stillbirths during the period 2006-08 to 2019-21 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2021).

Bury has the lowest preterm birth rates in its group of six statistical children service neighbours, with the highest rate in Sefton of 86.7 (Children and Maternal Health, 2021). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests an increasing rate of preterm births with increasing levels of deprivation. The most deprived decile in England has preterm birth rate of 87.8 compared with 76 in the least deprived decile for 2017-19 (Child and Maternal Health, 2021).

c. Neonatal Mortality

Preterm birth, intrapartum-related complications (birth asphyxia or inability to breathe at birth), infections and birth defects are the leading causes of most neonatal death. Children who die within the first 28 days of birth suffer from conditions and diseases associated with lack of quality care at or immediately after birth and in the first days of life. Neonatal Mortality is measured as a crude rate based on the number of deaths under 28 days per 1,000 live births.

In the period 2021-23, Bury's neonatal mortality rate was 4.5 per 1,000 live births, which was statistically higher than the England average of 3.0. Over the years, Bury's neonatal mortality rate has fluctuated possibly due to small numbers. Starting at 3.1 per 1,000 live births in 2010-12, it increased slightly to 3.5 in 2020-22 before reaching its current peak of 4.5 in 2021-23. The lowest rate for Bury was observed in 2018-20, at 2.6 per 1,000 live births. England's neonatal mortality rate has remained relatively stable, fluctuating between 2.7 and 3.0 per 1,000 live births over the same period. The highest rate for England was 3.0 in 2010-12 declining slightly to 2.9 in 2020-22. (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Neonatal mortality rate crude rate per 1,000 live births during the period 2010-12 to 2020-22 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2023).

Bury has the second highest neonatal mortality crude rate amongst its statistical neighbours for 2021-23, with the highest rate in Telford and Wrekin at 4.9 per 1,000, and the lowest rate in Bracknell Forest at 1.4 per 1,000 (Child and Maternal Health Profiles, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests an increasing neonatal mortality rate with increasing levels of deprivation. The most deprived decile in England neonatal mortality rate of 4.8 compared with 2.2 in the least deprived decile for 2020-22 (Child and Maternal Health Profiles, 2023).

d. Stillbirth Rate

Stillbirth rates in the United Kingdom have shown little change over the last 20 years, and the rate remains among the highest in high income countries. Risk factors associated with stillbirth include maternal obesity, ethnicity, smoking, pre-existing diabetes, and history of mental health problems, antepartum haemorrhage and fetal growth restriction (birth weight below the 10th customised weight percentile). In 2015, the government announced an ambition to halve the rate of stillbirths by 2030. Stillbirth rates are defined as the rate of fetal deaths occurring after 24 weeks of gestation, for all maternal ages, per 1,000 births in the respective calendar years. Stillbirth rate in Bury for the period 2021-23 was 5 per 1,000 births, statistically similar to England average of 4 per 1,000. The rate has steadily declined over time in both Bury and England. Stillbirth rate per 1,000 has decreased in Bury from 6.6 (its highest rate in the observed time period) in 2010-12 to its lowest rate of 3.8 in the periods 2016-18 and 2018-20 before rising to it’s the most recent rate of 5 per 1,000 in 2020-23 . The rate in England declined from 4.9 per 1,000 in 2010-12 to the lowest rate 3.9 in the periods 2018-20 to 2020-22 before rising slightly to the most recent rate of 4 per 1,000 (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Stillbirth crude rate per 1,000 births during the period 2010-12 to 2021-23 for Bury and England (Children and Maternal Health, 2023).

Bury has the fifth highest stillbirth rate in its group NHS England statistical neighbours, with the lowest rate in Warrington of 3 per 1,000 and highest in Rochdale of 6.8 per 1,000 (Children and Maternal Health, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests an increasing stillbirth rate with increasing levels of deprivation. The most deprived decile in England stillbirth rate was 5.1 per 1,000 for 2021-23, compared with 3.3 per 1,000 in the least deprived decile for the same time period (Child and Maternal Health, 2023).

e. Birth weight of babies

At a population level, birth weight is an indicator of multifaceted areas of public health importance that includes long-term maternal nutrition, health and health care in pregnancy. Birth weight or size at birth is an important indicator of the child's vulnerability to the risk of childhood illnesses and diseases. Birth weight also predicts the child's future health, growth, psychosocial development and chances of survival.

Fingertips present data on low birth weight for babies at term and all babies. Low birth weight has been defined by WHO as weight at birth of < 2500 grams (5.5 pounds). The causes of low birth weight are intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), premature birth, or both. It is closely associated with foetal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, stunted growth and cognitive development and NCDs later in life, among other negative health outcomesInfants with a low birth weight are approximately 20 times more likely to die than heavier infants (WHO, 2018).

Low birth weight of all babies

Low birth weight (LBW) of all babies is defined as all births (live and stillbirths) with a recorded birth weight under 2500g as a percentage of all live births with stated birth weight, regardless of the gestational age of the baby when born.

The proportion of LBW of all babies in Bury for the year 2022 was 8% statistically similar to England average of 7.2%. Data for Bury shows fluctuations with some increases and decreases. From the year 2010 to 2015, percentage of all babies with LBW declined from 7% to 5.8%. This was followed by a rise to 6.5% in 2016, steadily increased to 7.5% in 2018 and declining once again to 6.8% in 2019. A further decline in 2020 brought the figure for Bury down to its’ lowest for the observed time period of 5.7%, significantly better than the figure for England for 2020 of 6.9%. However, the two latest time periods have seen a further increase in Bury to 6.8% in 2021 and to 8% in 2022, the highest figure for Bury in the observed time period. The proportion for Bury has remained statistically similar to the England average throughout this time period, apart from 2015 (5.8% in Bury vs 7.4% in England) and 2020 (5.7% in Bury vs 6.9% in England), where the proportion in Bury was statistically lower than England average. The proportion of LBW in all babies in England has generally followed a downwards trend with a very slight decline from 7.3% in 2010 to 7.2% in 2022 (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Percentage (%) of low birth weight of all babies with a recorded birth weight under 2500g as a percentage of all live births with stated birth weight for Bury and England 2010 to 2022 (Children and Maternal Health, 2022).

Bury has the second highest proportion of LBW in all babies in its group of six statistical children service neighbours with the lowest proportion in Calderdale of 6.2% and highest in Stockton-on-Tees at 8.6% (Children and Maternal Health, 2022). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests a sharp deprivation gradient with increasing proportion of LBW in all babies as the levels of deprivation increases. The most deprived decile in England has 9% of LBW in all babies compared with 5.3% in the least deprived decile for the year 2021 (Child and Maternal Health, 2021).

Low birth weight of term babies

This indicator is consistent with the government's direction for public health, which emphasises prevention and early intervention. It has also been incorporated into the Department of Health's business plan in the context of addressing issues of premature deaths, preventable illness, and health inequalities, especially in relation to child poverty. It is defined as live births with a recorded birth weight under 2500g and a gestational age of at least 37 complete weeks as a percentage of all live births with recorded birth weight and a gestational age of at least 37 complete weeks. Unlike the previous indicator, this excludes babies born prematurely.

In 2022, the percentage (%) of low birth weight (LBW) term babies in Bury was 3.4%, which is statistically similar to the England average of 2.9%. The data for Bury shows fluctuations with minor increases and decreases over the years, with the trend showing no significant change. The percentage of term babies with LBW in Bury has slightly increased from 2.9% in 2006 to 3.4% in 2022. Throughout this period, Bury's proportion has remained statistically similar to the England average. Meanwhile, the proportion of term babies with LBW in England has gradually declined from 3% in 2006 to 2.9% in 2022 (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Percentage (%) of low birth weight of term babies with a recorded birth weight under 2500g and a gestational age of at least 37 complete weeks as a percentage of all live births with recorded birth weight and a gestational age of at least 37 complete weeks for Bury and England for 2010 to 2022 (Children and Maternal Health, 2022).

Bury has the highest proportion of term babies with LBW in its group of statistical children service neighbours with the lowest in Stockport at 2.1% (Children and Maternal Health, 2022). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests a deprivation gradient with increasing proportion of LBW in term babies as the levels of deprivation increases. The most deprived decile in England has 4% of LBW in term babies compared with 1.9% in the least deprived decile for the year 2022 (Child and Maternal Health, 2022).

e. Low birth weight of live babies, five year pooled data

This indicator is defined as percentage of all live births with a recorded birth weight under 2500g as a percentage of all live births with stated birth weight, pooled over five years. This indicator has been included as it is available at the ward level and provides valuable insights into geographical variations in Bury.

The percentage of low birth weight of live babies in Bury for the five year pooled data from 2016-20 is 6.2%, slightly lower than England average of 6.8%. Examining data by ward, the highest percentages of low birth weight of live babies are in Radcliffe North and Unsworth at 7.9% and Besses at 7.8% in the period 2016-20. The lowest percentage during the same time period is in North Manor (3.4%) and Pilkington Park (4.1%) (Table 1)

Table 1: Percentage of low birth weight of live babies in Bury wards, Bury and England (five years pooled data from 2016 to 2020) (Local Health, 2020)

f. Multiple births

Multiple births have significantly higher rates of stillbirth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, preterm birth, low birth weight, congenital anomalies and subsequent developmental problems compared to single births. Each of these has implications for families and society. Multiple birth rates are affected by differences in the percentages of older women who give birth, the extent of ovarian stimulation and assisted conception and other factors. They therefore contribute to geographical and temporal variations in infant and childhood mortality and morbidity rates.

Multiple births are defined as number of maternities where the outcome is a multiple birth expressed as a rate per 1,000 total maternities. The rate in Bury for the year 2022 was 14.1 per 1,000 total maternities, decreasing with slight fluctuations from a high of 19.3 per 1,000 in 2010. The trend in Bury shows a slight decrease in multiple birth rates between 2010 and 2022, with the lowest year for multiple births in Bury being 2020 when it was recorded as 11 per 1,000 total maternities. Data based on the five most recent data points do not show any significant change.

England has also seen slight fluctuations in the multiple birth rate from 15.7 per 1,000 in 2010 to 14.6 in 2022. The highest multiple birth rate in England was 16.2 per 1,000 maternities in 2011, and the lowest was 13.7 per 1,000 maternities in 2021. England has a decreasing trend in multiple birth rates based on the 5 most recent data points. (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Rate of multiple births per 1,000 total maternities for Bury and England for 2010 to 2022 (Children and Maternal Health, 2022).

Bury has the fourth highest multiple birth rates in its group of 6 statistical children service neighbours, with the lowest rate in Calderdale of 10.9 per 1,000 maternities and highest in Sefton at 16.4 per 1,000 maternities for 2022 (Children and Maternal Health, 2022). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data suggests a slight deprivation gradient. The most deprived decile in England has the lowest multiple birth rates at 13.8 per 1,000 maternities and the least deprived decile has the highest multiple birth rates at 16.8 in the year 2022 (Child and Maternal Health, 2022).

g. Admission of babies under 14 days

High admission rates of mothers or infants shortly after birth may indicate problems with the timing or quality of health assessments before the initial transfer or with the postnatal care provided once the mother returns home. Dehydration and jaundice are two common reasons for re-admission of infants and are frequently associated with feeding difficulties.

Admission of babies under 14 days are expressed as crude rates per 1,000 deliveries based on the number of emergency admissions from babies aged 0-13 days (inclusive). Admission rate for babies under 14 days in Bury for the period 2022/23 was 54.7 per 1,000 deliveries. There are wide variations in crude admission rates for babies under 14 days in Bury, with the highest rates in 2018/19 at 103.8 per 1,000 deliveries and the lowest in 2022/23 at 54.7 per 1,000 deliveries. The admission rates in Bury increased from 67.7 in 2014/15 to 103.8 in 2018/19, followed by a decrease to 69 in 2019/20 and a slight increase to 82.7 in 2020/21. This was followed by two periods of decrease to 74.4 in 2021/22 and further to the current rate of 54.7 per 1,000 in 2022/23 (Figure 15). Data based on the five most recent data points suggests that the admission rates are decreasing and getting better.

Admission rates in England increased from 60.7 per 1,000 deliveries in 2014/15 to 78.1 in 2019/20. This was followed by a slight decrease to 77.6 in 2020/21, followed by a further increase to 81/6 in 2021/22. The rate in England then increased to its highest rate for the observed time period to 84.8 per 1,000 for 2022/23. General trend for England over the most recent data points shows that the admission rates for babies under 14 days are increasing and getting worse (Child and Maternal Health Profiles, 2023).

Figure 15: Crude admission rate for babies under 14 days per 1,000 deliveries for Bury and England for 2013/14 to 2022/23 (Children and Maternal Health, 2023).

Bury has the lowest admission rates for babies under 14 days in its group of statistical children service neighbours with the highest rate in Stockport at 129.9 per 1,000 deliveries for 2022/23 (Children and Maternal Health, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level but England data shows the lowest admission rates in the most deprived decile at 77.8 per 1,000 and the highest rate in the least deprived decile at 84.6 per 1,000 deliveries (Child and Maternal Health, 2023).

3. Breast feeding

Due to the dynamic and interactive nature of breastfeeding and the unique living properties of breastmilk, human infants (12 months) and young children (aged 12–36 months) are most likely to survive, grow and develop to their full potential when they are breastfed by their mothers (Victoria et al, 2016). Breastfeeding is essential for preventing the triple burden of malnutrition, infectious diseases and mortality, as well as reducing the risk of obesity and chronic diseases in later life (Rollins et al, 2016). Breastfed babies are at a lower risk of gastrointestinal (due to gut protective bacteria in breast milk) and respiratory tract infections. When a baby breastfeeds, the mother's body releases hormones that prevent ovulation, resulting in lactational amenorrhea, which promotes birth spacing. Additionally, breastfeeding protects the mother from chronic diseases, such as breast and ovarian cancers, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The substantial, positive, early-life effects of breastfeeding on infants, mothers, families and society are sustained throughout the life course, with substantial economic benefits.

WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, continued breastfeeding for at least the first two years, and the introduction of complementary foods at six months postpartum. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) recommends babies are exclusively breastfed until around 6 months of age and continue to be breastfed for at least the first year of life. Additionally, solid foods should not be introduced until around 6 months to benefit the child’s overall health. Yet worldwide, many mothers who can and want to breastfeed encounter numerous barriers including structural barriers such as gender inequalities, harmful socio-cultural feeding practices, income growth and urbanisation and corporate marketing practices (Escamilla et al, 2023).

a. Babies first feed breast milk

First breast feed in babies is important as the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding begins with the first feed and the feeding of colostrum. Colostrum, a mother's first milk or the 'very first food', is a sticky, yellowish substance produced by the mother soon after birth. It is ideal for the newborn - in composition, in quantity and rich in vitamins and antibodies. Colostrum contains several concentrated properties which provide a protective coating to the lining of the gut preventing bacterial transfer.

This indicator is defined as percentage of babies whose first feed is breastmilk. Data are available for Bury for the period 2021/22 to 2023/24, although Fingertips does state that there are concerns with the quality of the data for this indicator due to the data collection methods. Percentage of babies whose first feed is breastmilk in Bury was 54.1% in 2023/24, decreasing from 59.5% in 2021/22 (Maternal and Child Health, 2023). England has seen a gradual decline during the same period from 72.2% in 2021/22 to 71.9% in 2023/24 (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Percentage of baby’s first feed breastmilk for Bury and England for 2021/22 to 2023/24 (Children and Maternal Health, 2023).

Bury has the second lowest proportion of babies with first feed breastmilk in its group of children's services statistical neighbours in 2023/24. The lowest proportion is in Stockton-on-Tees at 53.7% and the highest is in Calderdale at 71.4% (Maternal and Child Health, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level. Data at the national level suggests that as the levels of deprivation increases, the percentage of babies with first feed breastmilk decreases. The percentage of babies with first feed breastmilk in the most deprived decile in England is 59.1 compared with 81.3% in the least deprived decile in the period 2023/24 (Child and Maternal Health, 2023).

b. Percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups

A University of Manchester study on breast feeding rates in England found that white ethnic group mothers were 69% more likely to stop breastfeeding compared with non-White ethnic group mothers; they also breastfed for shorter durations compared with mothers from other ethnic groups. Other studies and surveys have shown that mothers from all minority ethnic groups are more likely to breastfeed compared with White mothers.

The percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups in Bury was 25.8% in 2022/23, statistically similar to the England average of 25.3%. Data for Bury shows some fluctuations, with an overall increasing trend based on the five most recent data points. The percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups increased from 15.5% in 2013/14 to 25.8% in 2022/23. This is the highest percentage recorded for Bury during the observed time period.The percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups in England increased from 20.7% in 2013/14 to 25.3% in 2022/23. The increase in Bury (10.3%) is more than double the increase for the same time period seen in England (4.6%) (Figure 17) (Child and Maternal Health, 2023).

Figure 17: Percentage of deliveries to women from ethic minority groups for Bury and England for 2013/14 to 2022/23 (Child and Maternal Health, 2023).

Bury has the highest percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups in its group of children's services statistical neighbours in 2022/23, with the lowest proportion in Sefton at 6% (Maternal and Child Health, 2023). There are no data on inequalities at Bury level. Data at the national level by LSOA deprivation deciles in England suggests a deprivation gradient with increasing percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups with increasing levels of deprivation. The percentage of deliveries to mothers from ethnic minority groups in the most deprived decile in England is 34.4% compared with 13.5% in the least deprived decile in the period 2022/23 (Child and Maternal Health, 2023).